A temple bell woke me up from jet-lagged sleep in my wonderful designer hotel here in Seoul. A few hundred miles away is the border with nuclear-armed Communist North Korea. It is all a useful reminder of how journalism is situated in a global, political and historical context.

It was the global and historical context of media change that I was trying to think through in a speech to the 50th anniversary conference of the Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies (KSJCS).

Here’s the text of that speech which draws on my previous thoughts on networked journalism and the end of fortress journalism, but adds a more theoretical flavour of the work of Roger Silverstone, Manuel Castells and Terhi Rantanen.

I was asked to talk about ‘online journalism’, but in a sense, I think there is now no other kind of journalism. By that I mean that anyone practicising journalism anywhere in the world is, in some sense, now conditioned by digital technologies and the Internet. We are all infected, as it were, by conditions or concepts such as citizen journalism, satellite transmission, search, infotainment and hypertextuality. All these are things undreamt of half a century ago. I think of this as technological climate change. Like global warming it is a man-made phenomenon, driven firstly by the old advanced economies and accelerated by emerging states. But, like climate change, its impacts are universal from the Antarctic to Africa. The whole world shares a new media environment and that ecology is now genetically digital.

Of course, anyone with any contact with diverse parts of our globe knows that the news media differentiates itself geographically. When I visit India I see booming newspaper sales and multiplying news channels. In its cities there is a booming consumer media while the Indian language press caters to an increasingly literate rural population.

When I go to California I see whole cities suddenly without newspapers and major national TV or newspaper companies that no longer have bureaux in major world cities. So media is in flux, but nowhere is it the same. This is good.

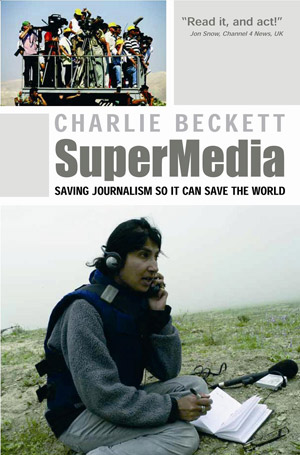

I believe that we are in the process of creating a more diverse and potentially more useful news media through a combination of new technologies and public participation. In my book SuperMedia I call it Networked Journalism.

Let’s take one unexpected example.

Let’s go to the world’s biggest slum, Kibere. It was a black hole in the media universe untouched by mainstream traditional media based a few minutes drive away in Nairobi. Until a couple of years ago, it was without any media.

These are citizens who can’t afford or can’t read newspapers. They are not important enough to feature in Kenyan mainstream media discourse which is vibrant but obsessed by mainstream politics. They have been disenfrachised as citizens in a world where politics is essentially conducted through or mediated by news communications.

This is a place where electricity is frequently cut off, where email and the Web is confined to a few internet cafes - and anyway, it is irrelevant for a slum that doesn’t figure on the world wide web - this is a place where state-provided landlines are pretty much defunct because of incompetence and corruption.

These outsiders have now found a voice through SMS. Through cheap mobile phone texting, its 500,000 people can begin a conversation with the volunteer journalists of a new community radio station Pamoja FM. The journalists use their mobiles to gather stories. Pamoja’s audience use their mobiles to text in stories, to ask questions and to request help. The right medicine is identified for a listeners illness. A lost child is located. A new store opening is announced. This is made possible by new technology. This is changing lives. This is changing journalism. And by changing journalism it goes further. It networks that community into wider Kenyan and international media and so into the wider, more powerful policy making of international NGOs, and Governments. So when Kenya was ravaged by internal violence 18 months ago, it was Pamoja FM that acted responsibly to report the conflict in a way that lessened rather than fanned the flames. It was a local media acting with an ethical responsibility beyond its boundaries. It could do this because of new media technologies that connected it in new ways to its public, but also to the wider world. This story is being repeated around the world.

I left the newsroom three years ago to create Polis, the media think-tank at the London School of Economics. This really is one of the most momentous phases for UK and Western Media. And, I would argue, for global media. So people are desperate for thought leadership on international news media and society, for critical analysis and insightful research. We don’t know what is going to happen next, but we know that what happens next matters.

I joined the LSE partly because of the inspiring work of a journalist turned academic called Professor Roger Silverstone. A month after I begun work at the LSE he died in a freak medical accident. His seminal posthumous work called Media and Morality is testament to his thoughtful and idealistic understanding of the importance of news media and his awareness that it is at a moment in history where its political and moral purpose was contested as never before. He was someone who thought that international news media should aspire to a Cosmopolitanism - a sense that journalism could contribute to a better understanding between different peoples in different places. But he was also acutely conscious, as a former journalist and as a critical scholar, that media can be a platform for both positive and negative forces. He made an extraordinary claim for journalism. He said:

“I want to endorse the idea of the media as an environment, an environment which provides at the most fundamental level the resources we all need for the conduct of everyday life. It follows that such an environment may be or may become, or may not be or may not become, polluted.”

(Professor Roger Silverstone, Media and Morality Sage 2006)

Now I want to take that text as the underpinning of what I want to say today. That is the reality of media today. That is the moral choice facing us either as citizens or as journalists. And as I shall explain, I think those categories are increasingly intertwined - or rather networked.

I want to try to answer a very big question today with a series of smaller questions. I am doing this because I think that we are at an unprecedented moment for journalism and journalism studies where we know only one thing for sure - things are changing and we do not know what will happen next. So all we can do as media researchers or analysts or practitioners is to think about and observe what is happening - all we can do is to ask the right questions.

I am convinced that Silverstone was right to ask such a fundamental moral question. We are a moment of profound change for the news media that raises transformational questions about the ethics, politics and economics of journalism. And journalism itself is a key to answering broader societal and global questions.

Journalism as we knew it is in danger and if we don’t save it’s core values and functions then we will struggle to deal with the complex problems facing the world such as climate change, economic crisis and migration.

In my book SuperMedia I explain how journalism is changing: it is now permeable, interactive, 24/7, multi-platform, disaggregated and converged. I could extend this list, but I will assume that you understand what is happening.

If you don’t believe that it has changed profoundly then come back with me less than 25 years to a newsroom with a fixed phone, a typewriter, a weekly deadline and a readership which had no access to the news except the information that I gave them. The only way they could interact was by writing me a letter which I would use to light a cigarette. Oh yes, we could smoke at our desks, too.

The technological changes are impressive. Take these examples.

The Twitter alerts of tourists who witnessed the Sechuan earthquake that scooped the world’s media and unsettled the Chinese government.

The mobile phone images of Saddam Hussein’s grisly execution that punctured American hopes to present the world with the story of a clean judicial death.

The Guardian newspaper - a small circulation liberal British newspaper that now has millions of readers online in America.

You will have countless examples yourselves, I am sure. I am not here to convince you that new media technologies are transforming journalism.

What I want to do is to say is that journalism must continue to change more profoundly in its editorial ethos and its social role if it is to survive and thrive in this digital future.

We can use new media technologies to transform our journalism. It means building public participation into all aspects of journalism. It means encouraging user generated content, promoting interactivity and sharing the news space. It means accepting that the old business model is broken and that we have to justify the value of journalism again.

That means transforming the way we do journalism but it also means recasting our values as journalists – economic, editorial and political.

It means shifting from being a manufacturing industry to a service industry.

It means changing what we do from creating product to facilitating a process.

It is much more than simply taking the existing newsroom online.

It is what I call Networked Journalism.

The good news is that people want this. That is why they send in 60 000 images to the BBC during 48 hours of heavy snow last month. This is why they write blogs, edit films for YouTube and construct social networks online. They want to take part in a conversation about their world and the way that they live their lives. Journalism task is to facilitate that conversation.

People want the diversity of the blogosphere – but they also want the editing, filtering and packaging functions that journalism performs. They want the reporting, investigation, analysis and information that journalism can facilitate whether produced professionally or unpaid.

I can think of no other business where the consumer is prepared to create content for free and yet where the producers complain about that.

So why is our business failing?

I think it is partly because there is still too much duplication. Journalists create too much material that is available more easily elsewhere. We create too much formulaic, boring and irrelevant content.

There is too much journalism that does not add value and is not relevant. It is being exposed and it will disappear. That’s going to be painful.

Too many organisations have gone on line and chased the easy traffic. Some of them will succeed but not everyone can cover showbusiness, celebrity and sport.

Too little has been invested in real networked journalism. The old media owners have been too keen to protect their profit margins instead of investing in connecting with new communities and providing the citizen with a product that is of real value to them.

There has been some outstanding innovation and hard work in the face of the challenge of media change – but collectively there has been a failure of imagination and a reluctance to understand the full extent of what is happening.

Journalism has never been more needed and more in demand and yet journalists are struggling to sustain business models that will deliver this product.

What is the way forward?

We have to end Fortress Journalism. We have to break down the walls of news institutions and make new partnerships with the citizen.

This is partly by engaging the citizen in every aspect of journalistic production. That way you will produce something that people can trust, use and support.

We can also do it through through partnerships with NGOs, with business, with government, with community groups or with foundations or with universities or schools or with other independent media.

Social groups, business and government are all becoming more networked – all organisations are turning into media organisations in some way – journalism can be part of that process. It means taking journalism out of the newsroom and into offices, schools, hospitals and homes.

Journalism has to go environmental, in Silverstone’s phrase. Or to take another philosopher of new media, it must become part of the culture. In his forthcoming book, Communication Power (OUP, 2009) Manuel Castells outlines how society is remaking itself as a series of networks:

“Networked individualism is a culture, not an organizational form. A culture that starts with the values and projects of the individual but builds a system of exchange with other individuals, thus reconstructing society rather than reproducing society.” (Castells Communication Power, 2009)

This will challenge the traditional role of journalism as a separate Fourth Estate but I think this has always been something of a myth. Journalists have savoured the power that separation brings, but we never really accepted the responsibilities that it entailed.

Journalism has to make a new contract with the citizen. In the past the deal was that journalism was allowed to do some good and much poor work in return for advertising or tax subsidy.

Now it has to make a make the case for journalism as an agent of public value and a part of people’s lives in an age where people have shown that they want media to act on their behalf, not that of media shareholders or professional cliques. In return they will support what we do.

Now if a news media organisation thinks that it is up to date because it blogs or is online then it must think again. And here , journalism have a critical role in enhancing a reflexive understanding of media change to help this process of reinvention.

Being Networked means much more than just public participation in what you do as a journalist. Now the journalist will have to go to where the citizen is.

Just when you thought you had got used to Web 2.0 here comes the next leap forwards. And it is not really about technology. It is social networking. Facebook is not a website – it is a platform. Media and communications in general is moving into social networks – journalism has to go there too.

We have no choice as journalists. We either Network or die.

Now as journalism educators we must explain and understand these profound facts. We must attend to these shifting definitions. Our own frameworks for understanding how media works and its effects must be reconfigured. We are being set new research questions.

We must understand how Temporality is changing. With the death of the deadline comes multi-dimensional narratives.

With the death of distance comes new flows of information. The world is interconnected, and that connectivity reverses the direction of ideas as well as data.

And with public participation comes a redistribution of knowledge and creativity. Media literacy must be part of every curriculum but the autodidactic also thrives in a networked world where enpowerment itself is suddenly disintermediated.

My aim today is not to explain these idea thoroughly. I am throwing out suggested areas for further research. But I want to end by insisting that this is an unusual and important historic moment. It doesn’t matter if you come from a country with, for example, low internet penetration or from a city without broadband. The point is that everywhere will be effected at some point - in different ways - but profoundly.

As my colleague Terhi Rantanen has summarised in her recent book, When News Was New (Wiley-Blackwell, 20009) we can see how the very idea of news itself is shifting again.

This has happened before - look at how the mass media was created by news agencies and then the growth of broadcasting in the 20th century.

And it is not just about new technologies - many of the new media trends build on wider social developments such as increasing levels of education, the spread of liberal market economics and the growth of consumerist individualsim.

But as I outline in my book SuperMedia (Wiley-Blackwell 2008) the shift to networked journalism is a shift in power as well as a shift in practice.

But as I outline in my book SuperMedia (Wiley-Blackwell 2008) the shift to networked journalism is a shift in power as well as a shift in practice.

Rantenan identifies four developments reshaping the definition of news:

1. The difference between events and news is disappearing

2. The difference between information and news is disappearing

3. The difference between news and comment is disappearing

4. The difference between news and entertainment is disappearing

Of those four developments, I think that the first is the most important. You only have to think for a moment about spin and political news to realise how rarely stories are about facts or something actually happening. But I would insist that the biggest different is not those developments in content definition. The biggest development is in the mode of production. News used to be linear and now it is networked. That is what will remake the meaning of news.

We are going to lose more than just traditional news organisations. We are going to lose more than just traditional news practices. We are going to gain a whole new way of making news. We are in the process of reinventing the idea of what news is itself. That weird formulaic culture which was constructed essentially through advertising may be at an end. And that might be a good thing. This is Rantanen’s fascinating conclusion which I will now use to make mine:

“Considering the historical trajectory of news from news hawkers in the Middle Ages to bloggers in the Information Age, it is possible to argue that we are now witnessing the death of ‘modern news’, as conceived in the nineteenth century. In this situation of multiple change, serious thought is required about what consitutes news. Everybody thinks they know what news is, but in fact nobody can define the twenty-first concept of news. The boundaries are again becoming blurred. News may again become just new stories” (Rantanen 2009).

Charlie Beckett